Royston and Stein Gardens

Mill Valley, California, 1947-Present

For over sixty years Robert Royston’s garden in Mill Valley, California was his laboratory – an ever evolving testing ground for his ideas about planting, spatial composition, construction materials, furniture design, and the needs of family living. Innovative from the start, the garden morphed seamlessly over the decades in response to shifts in personal need and the inevitable changes wrought by time. A setting for a remarkable range of activities; children’s birthday parties, academic conversations, client presentations, and afternoons of friendly chatter over wine and a game of bocce ball or pétanque, the gardens accommodated a life lived to a great degree out of doors. Such a lifestyle would become synonymous with California in the popular imagination by the latter half of the twentieth-century, but in the immediate postwar period it was a concept that was just beginning to emerge from the work of a new generation of designers that included Robert Royston and his friend and architect colleague Joseph Allen Stein.

In 1945 Eckbo Royston &Williams shared office space at 50 Green Street in San Francisco with young architects Joseph Allen Stein and John Funk. Friends as well as professional colleagues the principals of both firms would go on to work collaboratively on a regular basis gaining a reputation for thoughtfully detailed and innovative single-family residential projects.

In 1945 Eckbo Royston &Williams shared office space at 50 Green Street in San Francisco with young architects Joseph Allen Stein and John Funk. Friends as well as professional colleagues the principals of both firms would go on to work collaboratively on a regular basis gaining a reputation for thoughtfully detailed and innovative single-family residential projects.

© Rainey, Reuben M., and JC Miller. Robert Royston. 2020. “Concept plan of the two gardens, 1947.” Photograph. The University of Georgia Press, 2020.

In 1946 Stein located a hillside parcel in that he felt would meet their needs. Located in then sparsely populated and semi remote Marin County, the nearly three acre site was situated on a wooded north facing slope with views across the valley toward Mt. Tamalpais. After visiting the lot Royston agreed that it was ideal for the project, so it was purchased and planning for a pair of homes began. The gardens that resulted were remarkable, not only for the innovative modern design that nurtured both families, but also for influence that they would have on residential landscape design for nearly a decade. The architecture of the homes received nearly immediate positive professional attention, appearing in both Architectural Forum and Arts & Architecture magazines by mid 1949.Concurrently Royston’s garden designs drew critical praise and were published frequently, first locally in the SF Chronicle and Marin Independent Journal newspapers and then regionally in Sunset magazine. The gardens appeared regularly throughout the 1950’s in homeowner oriented books from the Lane Publishing Company, the parent company of Sunset Magazine.

Architectural Design

These twin house on a Marin county hillside enabled Stein to put into physical form ideas about family housing that he began to develop in the late 1930’s while working in Los Angeles in Richard Neutra’s office. During that time he had begun to explore modest and compact structures inspired by the work of his mentor Neutra and Bay Area architect William Wurster. The October 1940 issue of Architectural Forum magazine, titled ‘Design Decade’, included Stein’s plan for a low cost housing prototype with a series of spaces rotated 45 degrees within a square building, an idea that he continued to develop this idea after his move to the Bay Area in 1942. His plan for a low cost single family home that was included in the San Francisco Museum of Art’s ‘Houses for War and Post-War’ exhibit displayed in that same year bears a strong resemblance to the homes that he would build in collaboration with Royston.

© Rainey, Reuben M., and JC Miller. Robert Royston. 2020. “Paved terraces on south side , c. 1955 Photo by ErnestBraun, EBA.” Photograph. The University of Georgia Press, 2020.

The basic footprint of each of the Mill Valley homes was a square with a small angled extension. A single flat roof plane covered the living space and extended over the adjacent parking area and beyond the living space perimeter to provide deep overhangs over predominantly glass walls. Within the perimeter of the homes the floor plan was rotated 45 degrees to the walls around a central fireplace. This unusual arrangement of interior spaces resulted in rooms with long walls adjacent to the exterior walls ideal for maximizing the connection between the home’s interior and the landscape. In Stein’s plan the living room, dining room, and kitchen as well as adult and children’s sleeping areas all opened to patios and the gardens beyond.

Design of the Gardens

Royston addressed the two gardens as a single design. While each has a distinct character and reflects the preferences and needs of their respective owners, there is a unity to the initial design that is unusual in neighboring properties. While it differs in some ways from the built work, the concept plan that he prepared clearly shows his intention to create subtle relationships between forms not only within each garden, but between the two. The Royston garden on the left of the drawing shows a slightly more informal and asymmetrical arrangement of planting and patio spaces while in the Stein garden to the right features adhere more closely to a geometric layout and parallel lines more closely related to the architecture.

Although the gardens depicted in the concept plan were never fully realized as drawn, the detailed representation of outdoor spaces, the size, form, and texture of planting, and the extension of lines originating in architecture into the landscape are clear indications of the approach to garden design that Royston explored throughout his career.

The concept plan clearly expresses his emphasis on connection between the rooms of the home and corresponding outdoor spaces. The result of this design strategy was spaces that were highly integrated and complex with the dividing line between the two intentionally ambiguous. At both homes the entry sequence begins with what appears to be a rather traditional looking door that is actually a gate opening to a garden room. The visitor is then led through a walled space open to the sky before he or she moves indoors. The freestanding panel wall, a repetition of the building’s structural system reinforces the hybrid nature of the space.

Although the gardens depicted in the concept plan were never fully realized as drawn, the detailed representation of outdoor spaces, the size, form, and texture of planting, and the extension of lines originating in architecture into the landscape are clear indications of the approach to garden design that Royston explored throughout his career.

The concept plan clearly expresses his emphasis on connection between the rooms of the home and corresponding outdoor spaces. The result of this design strategy was spaces that were highly integrated and complex with the dividing line between the two intentionally ambiguous. At both homes the entry sequence begins with what appears to be a rather traditional looking door that is actually a gate opening to a garden room. The visitor is then led through a walled space open to the sky before he or she moves indoors. The freestanding panel wall, a repetition of the building’s structural system reinforces the hybrid nature of the space.

© Rainey, Reuben M., and JC Miller. Robert Royston. 2020. “View of patio from bedroom, c. 1955 Photo by Ernest Braun, EBA.” Photograph. The University of Georgia Press, 2020.

Although less literally, other walls of the homes were brought out into the landscape, generating outdoor spaces that were rooms without roofs. Royston was bold about pushing a line or plane that originated in architecture out into the landscape and his patio design reinforced the strategy by extending the ground plane with only the minimum necessary drop in elevation from the interior floor.

Planting as Painting and Sculpture

While Royston’s early concept plan for the new gardens does not indicate specific plant materials, it clearly indicates his intention for a complex planting design with considerable variety in size, form, texture, and presumably color. Royston’s approach to planting design was certainly grounded in a strong knowledge of the fundamentals of botany and climate, but it went well beyond horticultural pragmatism. His background in painting and interest in sculpture informed his planting design choices and the selection of various plant varieties to a great degree.

A series of Sunset magazine articles that appeared between 1950 and 1952 provide a detailed description of the color combinations found in the first iteration of the Royston garden.

As a landscape architect, Royston understood the challenge of a medium that was constantly changing over time. The immature trees and shrubs in the initial planting in a garden or park could hardly define space effectively. In response to this situation he often employed architectural features such as walls, pergolas, and screens. He reinforced these architectural elements with vines and shrubs, which would develop in concert with trees to eventually provide nuanced and powerful spatial definition. The sixty plus years that unfolded during his life in the garden that he designed allowed him the opportunity to experience firsthand, and in intimate detail, the process of change over time.

While conceived as a single composition, the trajectories of the Royston and Stein gardens diverged not long after they were created and each developed in response to the families that dwelled there across a shared driveway. Both places experienced the addition of features, the development, decline and removal of planting, and the eventual passing of their creators. But, while the Stein house and garden remained relatively static over time with its composition and spatial relationships holding more or less to the original forms, the Royston home and garden experienced a process of almost continuous evolution. This can be explained by the fact that, Joseph Stein departed to India to serve as the Head of the Department of Architecture at Bengal Engineering College in Calcutta in 1952. Although he would return from time to time to visit his one-time neighbors, Stein never again lived in the house he had designed. Eventually the property passed into the hands of a current owner who appreciates its nature and has acted as a thoughtful steward, affecting little change. Across the driveway however, the Royston portion of the property reflects the remarkable consequences of decades of attention and experimentation by one of the twentieth-century’s most talented landscape architects.

A series of Sunset magazine articles that appeared between 1950 and 1952 provide a detailed description of the color combinations found in the first iteration of the Royston garden.

As a landscape architect, Royston understood the challenge of a medium that was constantly changing over time. The immature trees and shrubs in the initial planting in a garden or park could hardly define space effectively. In response to this situation he often employed architectural features such as walls, pergolas, and screens. He reinforced these architectural elements with vines and shrubs, which would develop in concert with trees to eventually provide nuanced and powerful spatial definition. The sixty plus years that unfolded during his life in the garden that he designed allowed him the opportunity to experience firsthand, and in intimate detail, the process of change over time.

While conceived as a single composition, the trajectories of the Royston and Stein gardens diverged not long after they were created and each developed in response to the families that dwelled there across a shared driveway. Both places experienced the addition of features, the development, decline and removal of planting, and the eventual passing of their creators. But, while the Stein house and garden remained relatively static over time with its composition and spatial relationships holding more or less to the original forms, the Royston home and garden experienced a process of almost continuous evolution. This can be explained by the fact that, Joseph Stein departed to India to serve as the Head of the Department of Architecture at Bengal Engineering College in Calcutta in 1952. Although he would return from time to time to visit his one-time neighbors, Stein never again lived in the house he had designed. Eventually the property passed into the hands of a current owner who appreciates its nature and has acted as a thoughtful steward, affecting little change. Across the driveway however, the Royston portion of the property reflects the remarkable consequences of decades of attention and experimentation by one of the twentieth-century’s most talented landscape architects.

Evolution of a Garden

The Royston garden has seen several distinct phases of development since its creation in 1947. These include the initial period of design and construction, embellishment of that initial design, changes made in response to the needs of a growing family, reorientation of the garden toward Mt. Tamalpais, and an extended period with little change other than the growth of trees followed by an active editorial period. Through each of these episodes Royston’s hand guided the changes to the garden.

Initial Design (1947 – 1950)

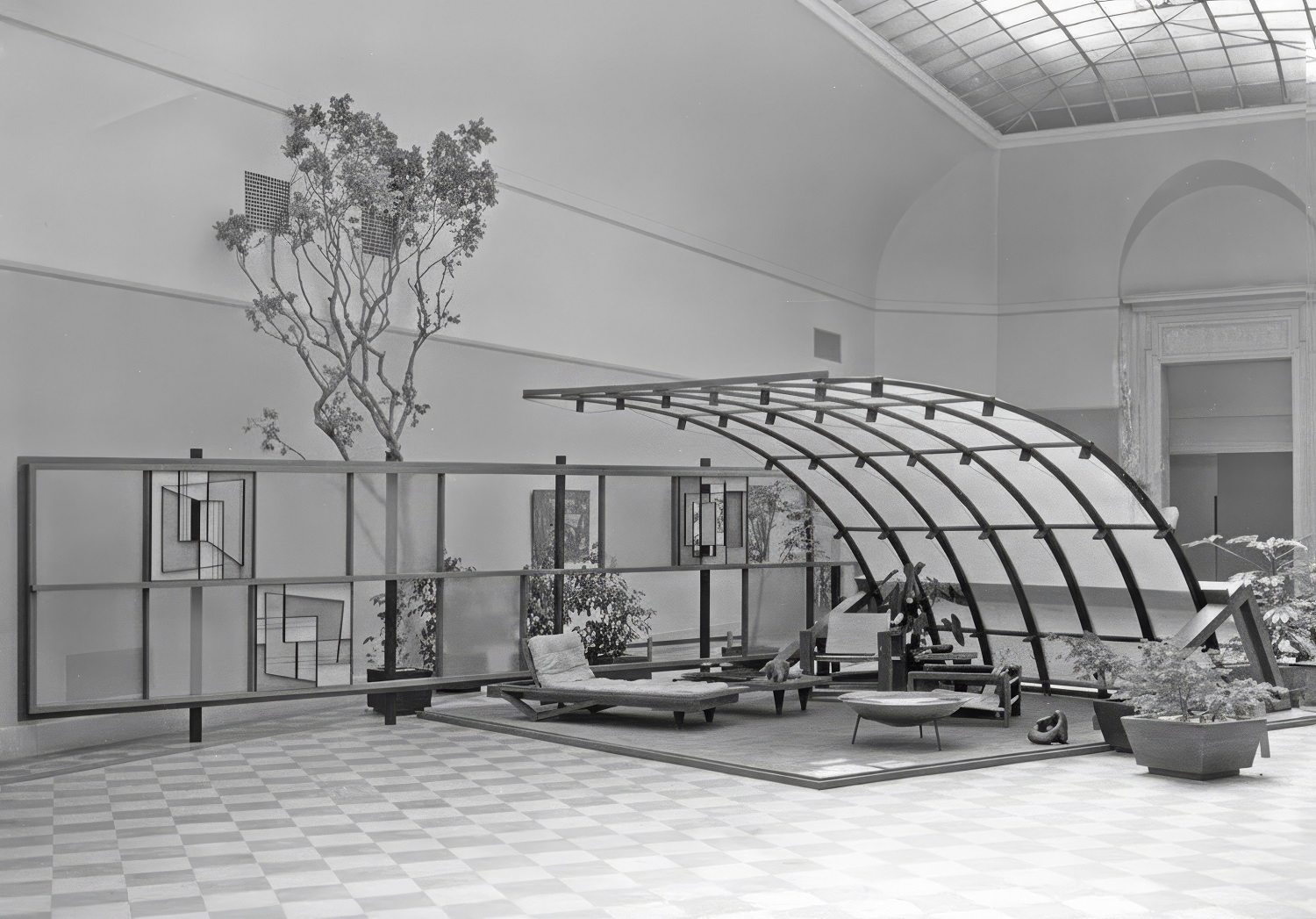

© Rainey, Reuben M., and JC Miller. Robert Royston.2020. “Garden screen installed at Design in the Patio exhibition, 1949.”Photograph. The University of Georgia Press, 2020.

The initial iteration of the garden shows a strong emphasis on spatial relationships and dynamic lines. Because of its prominence in the original design and its longevity in the garden, the art screen wall that separates the north garden from the laundry and service area merits special attention. Royston designed and built the screen to showcase sculptural tiles made by artist Florence Swift whom he had met while employed in the office of Thomas Church before leaving for military service.

Royston recalled later in interviews that he admired her work from the outset and hoped to eventually have several pieces. His interest in her work was strong enough that he prepared a number of study drawings at that time in which he worked out ways to incorporate the artist’s sculptural panels into garden structures. This was Royston’s first interaction with a professional artist, an aspect of his work that he would develop with great success. Over the course of his career he would collaborate on both private and public work with such notable artists as Claire Falkenstein, Benny Bufano, Ruth Asawa, and Henry Moore.

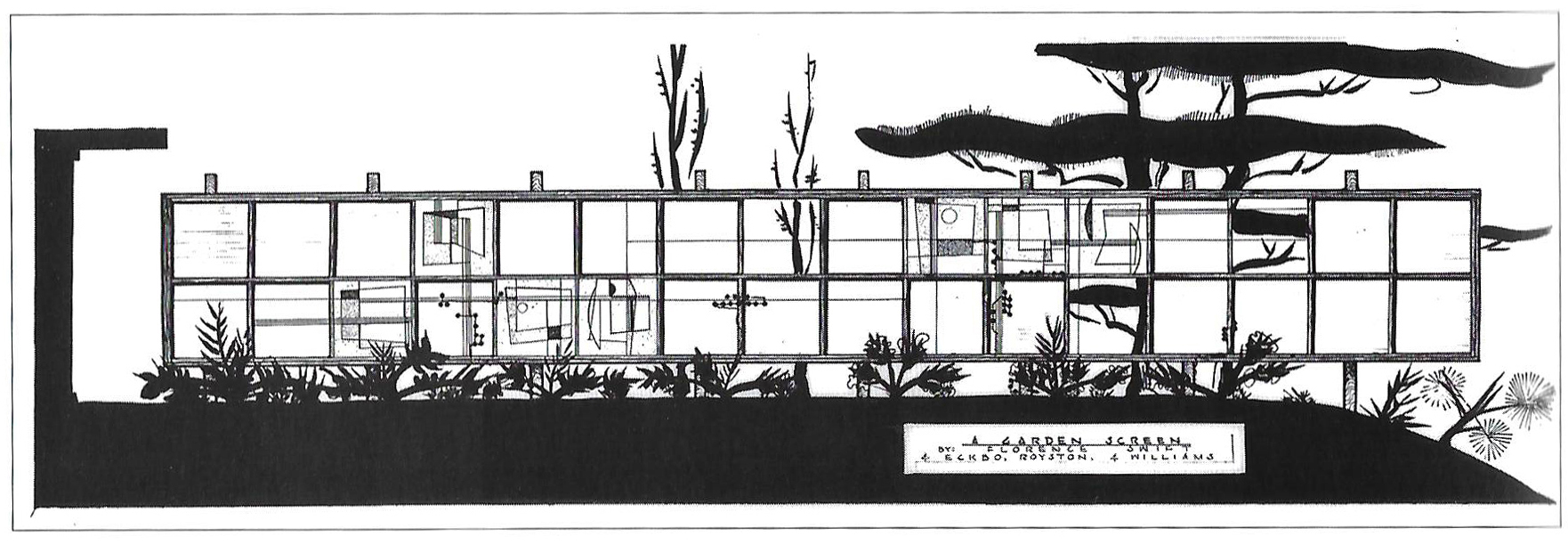

© Rainey, Reuben M., and JC Miller. Robert Royston. 2020. “Sketch of garden screen. From Eckbo, Landscape for Living (1950).” Photograph. The University of Georgia Press, 2020.

One of Royston’s study drawings for the garden eventually appears in Garret Eckbo’s Landscape for Living, published in 1950. It is interesting to note that the screen of Royston’s imagination was considerably longer and incorporated more of Swift’s tiles than the eventual built structure. In 1949 Eckbo Royston & Williams was asked to contribute to an exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Art entitled “Design in the Patio”. This afforded Royston the opportunity to realize the art screen wall that he had envisioned. He built the screen as well as the furniture for the exhibit at his new home in Mill Valley with the idea in mind that all would return and become part of the garden.

Over time, the house was expanded to accommodate the growing Royston family. The car port adjacent to the house was enclosed for a new bedroom suite for the parents and a new parking structure was added at the bottom of the newly paved driveway. These changes created a courtyard space outside of the new master bedroom with a greater sense of enclosure. The orientation of the new carport and the addition of Coast Redwoods framed the northward view out from the courtyard toward Mt. Tamalpais.

Over time, the house was expanded to accommodate the growing Royston family. The car port adjacent to the house was enclosed for a new bedroom suite for the parents and a new parking structure was added at the bottom of the newly paved driveway. These changes created a courtyard space outside of the new master bedroom with a greater sense of enclosure. The orientation of the new carport and the addition of Coast Redwoods framed the northward view out from the courtyard toward Mt. Tamalpais.

Bringing Mt. Tamalpais into the Garden

The addition of an expansive deck with studio space below realized the cap stone of the design and integration of the garden into greater landscape. Changes made a decade earlier had directed the views from the house and terraces toward Mt. Tamalpais and with the addition of the deck the connection between the garden and the mountain was made complete.

© Rainey, Reuben M., and JC Miller. Robert Royston. 2020. “View from the hill behind Stein home with wrist and home in background, Mount Tamalpais in distance, 1947.” Photograph. The University of Georgia Press, 2020.

Reached by a set of three broad shallow steps, the nearly 60’ long deck created a promontory experience and allowed for a dramatic view across the valley. Royston furnished the deck with built-in benches and tables and tucked a new design and art studio beneath it. Japanese Maples and additional Redwoods appeared in the garden while the planting in general was simplified.

In the early 1990's Royston reduces his professional activity and turns his attention back to his garden. An editing process begins that brings light back into the garden and reveal its fundamental structure. This work included the removal of a number of large trees and shrubs. Ivy that had become rampant is also removed and the art screen is restored to prominence. The now decrepit work room is removed and the slab foundation is re purposed as a rose garden. The lowest portion of the garden is cleared and decomposed granite is installed as a surface for games of Bocce or Petanque.

In the early 1990's Royston reduces his professional activity and turns his attention back to his garden. An editing process begins that brings light back into the garden and reveal its fundamental structure. This work included the removal of a number of large trees and shrubs. Ivy that had become rampant is also removed and the art screen is restored to prominence. The now decrepit work room is removed and the slab foundation is re purposed as a rose garden. The lowest portion of the garden is cleared and decomposed granite is installed as a surface for games of Bocce or Petanque.

Conclusion

The garden that Robert Royston designed and maintained for himself and his family holds a special place in the catalog of his professional output. While much of his work has endured for decades, a notable achievement given the sometimes ephemeral nature of the designed landscape, the hillside garden in Mill Valley has lasted longer than any other. While it has certainly evolved over the nearly seven decades since its inception, the original design vision seen in his earliest concept sketches is still legible and clear. Over the course of his long career Royston designed hundreds of gardens, parks, and urban spaces and in many of these places glimpses of ideas first explored in his own garden can be seen as features developed and expanded to suit the scale and purpose.

Contact Us

Please email us, We're happy to provide more information.

.svg)